WILDLY FREE ELDER

The Artistry of Aging

Engaging With The Wild

“The payment now is the sacrifice of certainty and control that comes in engagement with the wild. That is what renews the world.”

~Charles Eisenstein

“Engagement with the wild” inside, and outside, seems to be something we have forgotten how to be and do. As elders becoming it is an integral part of the initiation.

The wild in this case meaning inhabiting a space of being that holds no certainty, control, or what we have called “normal” within our patterned ruts deeply grooved in the matter of our brains.

The question we are all faced with right now. Do we adventure into new territory engaged through a courageous leap, stepping over the threshold of curiosity, into the heart of our own wildness?

Perhaps fitting in and belonging is more important right now. I understand the lure in such uncertain times. But haven’t they always been uncertain?

As Charles Eisenstein says, it is “time to devote ourselves to love rather than safety, beauty rather than growth, participation rather than control”. And perhaps, I say, be more inclusive rather than dismissive.

Imagine a large circle with 5 concentric circles within gradually reducing in size until the last one is simply at the center.

As humans we are prone to focus on two ways of thinking and survival. The outermost circle is focusing on the complexity of life through solving a problem or banishing a symptom which is a never ending loop of chasing after the next one that emerges. It certainly gives the mind endless jobs to do!

The second circle inside the first outer layer involves functions of mind, body heart – the operating systems if you will – which is a little more expanded, but still contained within the boxes of what is presently known about these operating systems and can endlessly be broadcast as mainstream and cultural dogma giving you that assumed sense of safety, certainty and control.

The next two circles and the very center are steps into engaging with the wild.

Engaging, innovating, imagining and creating new stories for ourselves, and by default all that we are interconnected with. And have fun doing it!

Moving out of “function” we enter into the energy of all life, where we are aware that the whole is always where we belong. Within that energetic space there is so much more room to play and let go. To practice our artistry without the restraints of external complexity and old operating systems theories clouding the playing field.

It may seem too vast in those first fall on your face moments to sense everything as energy flowing, but the next circle entices with expanded awareness and creativity, where embodied life just seems to increase in diversity and possibility for transforming old structures into new landscapes for fluidity, creative renewal and collaboration.

At the center of it all is ESSENCE. This is where the core of our being resides and holds court over our lives if we choose to live from that place of wholeness. We bypass the analysis and complexity of functions and go straight to the deepest cause of what may be blocking our way to engaging with the wild.

Like the wave above that has taken its own journey onto the beach away from the other structured molecules of water and minerals, we have the opportunity to finally come home to our unique offerings. Some part of that renegade portion of the wave will undoubtedly commune with sand, air and sun transforming and renewing its very being.

What wild engagement awaits you?

Gratitude to Mingtong Gu of Wisdom Healing Qigong for the image of 5 concentric circles in the Pure Consciousness foundation.

.

Interview with Andy Kidd, Brisbane, Australia

We invite you to listen to Wildly Free Elder, Gaye Abbott, as she interviews Andy Kidd talking about Life Lessence individualized personal and group legacy books; mentor Jim Ede in Scotland and the lessons he taught a 21-one-year old young man; and what it means to live well. Enjoy!!

What We Don’t Talk About

“I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?”

Mary Oliver, From A Summer’s Day

The Buddhists call it “impermanence”. We are all aware that everything changes and is always either , being birthed, breaking down or dying. All in the mystery of life unfolding.

Yet, what is our relationship with the indisputable fact that our physical bodies will eventually cease to be here? Yes, our own mortality.

In a time of global pandemics, climate change, and upheaval of systems and social standards that are ripe for major overhaul, we are faced even more with our own eventual physical death. As well as shedding of identities that perhaps fit more into what is breaking down than who we are becoming.

Last year an accidental fall over a gas nozzle hose, connected to my car that I attempted to step over, landed me head first on cement. Through an ER visit where broken bones and a subdural hematoma were ruled out, I realized that in an instant physical life as we know it can change dramatically.

Though there were no broken bones and my brain was counted as “normal”, once I returned home I was incapacitated and in shock needing assistance to dress and do the simplest of basic living tasks. It was then that I realized that it wasn’t death that I was afraid of, but loss of independence. This need for assistance lasted only for a few days, but it left its mark on me.

Accepting our own death, and that of our loved ones, is a unique journey all of us make. It cannot be avoided, especially as we age. We are an intimate part of the cycle of life, death and regeneration.

As elders we can choose to celebrate the essence of who we are now and share that wisdom, artistry and life experience with everyone we come in touch with, or we can follow the dominant culture and be terrified of our own mortality.

“We have created a global dominant culture which is terrified of its’ own mortality, so we lock our old people away”

From Giving Back To The Earth, A Video by Green Renaissance

It is normal to be afraid of our own death and hopefully take the time to have a relationship with it and support others in that process. But we have very little control over how and when our eventual demise will happen. As one woman says in the short video below – “If you are not conscious that you are going to die, then you are not fully alive”.

As Mary Oliver wrote in “A Summer’s Day”, “Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon. Tell me, what is it you plan to do with this one wild and precious life?” That is a question to live in every single moment you are blessed with no matter what age you are.

What do you want to leave behind? How do you want to be remembered?

Where are you placing your attention?

What do you want to do with the energy left to you?

A COUPLE OF RESOURCES:

The Green Burial Guidebook, Everything You Need to Plan an Affordable, Environmentally Friendly Burial by Elizabeth Fournier.

Life Lessence Legacy – personalized legacy books with Andy Kidd.

Die Wise by Stephen Jenkinson

Aging With An Attitude of Incline With Ramona Oliver

WELCOME to our newest Wildly Free Elder Spotlight, Ramona Oliver ! Please go to her page and see how Ramona is contributing to the Wildly Free Elder community and positive aging everywhere….and check out her book, Inclined Elders. too!

“Inclined Elders are men and women who have made a conscious choice to ignore society’s mindset of ‘decline’ and ‘over the hill’ as they age and have embraced an optimistic mindset of continuing to climb ever upwards. Inclined Elders: How to rebrand aging for self and society by Ramona Oliver gives a positive perception of aging and the Inclined Elders in this book leave their own unique legacies of wisdom and inspiration for future generations to understand. The book is a useful tool for readers to have a good attitude and mindset about aging, live a life of meaning and purpose, and leave a legacy to serve as role models to the coming generations. The tips, techniques, and strategies will encourage readers to live life with an open mind and not blindly accept and follow the norms laid down by society. The book has been divided into three sections – Attitude (Internal Focus), Growth (External Focus), and Empowerment (Societal Focus) – and shows readers how to live a life of ‘Incline.’

The author shares illustrative stories that speak about the everyday lives of people who are living a life of Incline. The book is also all about accepting change and embracing it, and adopting a positive attitude from adulthood to elderhood. Ramona Oliver also speaks about the attitude of the younger generation towards aging. I like the manner in which the topic has been discussed, keeping in mind the pertinence and the seriousness of it, thereby giving aging people the confidence and encouragement to look at life with a renewed perception that is positive and optimistic. The author has shared many interesting resources too in Inclined Elders, and these are engaging and thought-provoking and can be considered when starting to live life as an Incline.”

Reviewed by Mamta Madhavan for Readers’ Favorite: 5-star Review

Breakfast With Jim

Breakfast with Jim

Guest Blog Post by Andy Kidd

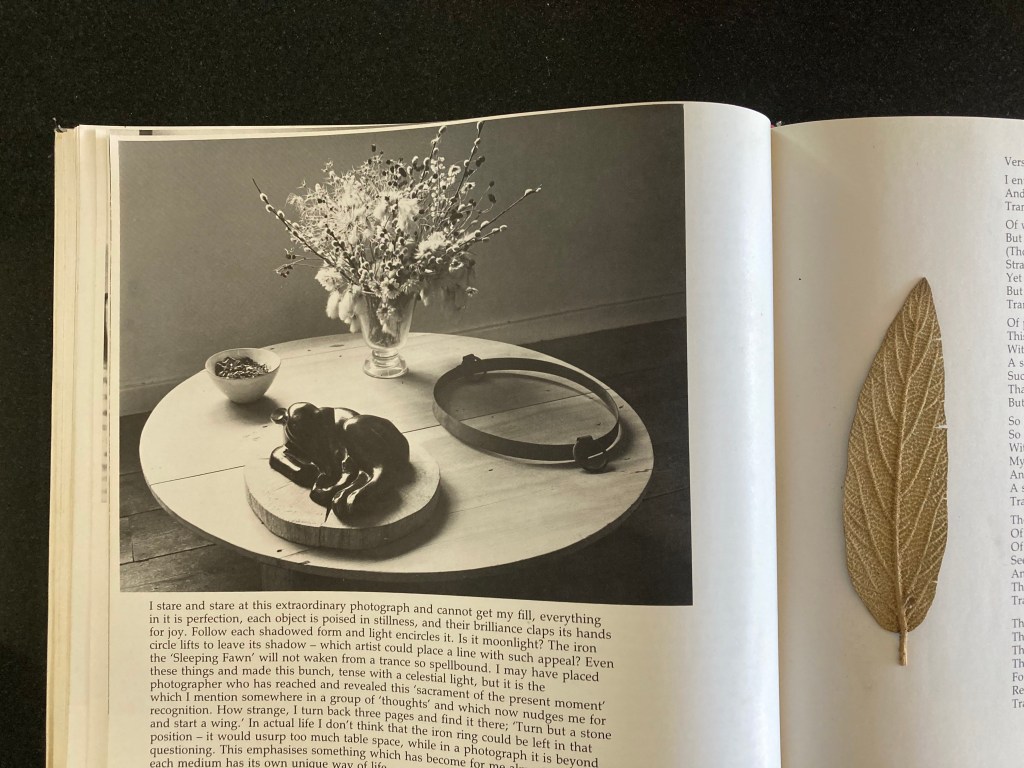

Hanging on a string by Jim’s door, a wide flat cork with instructions to ‘Pull gently’ rang an old iron bell. I paused outside to look at the stones laid in gatherings which covered his window sills and made borders for his flower beds and lawn. Pebbles and rocks, eroded by time, collected on beaches over a lifetime: many Jim found on Tiree. Piled together, they might have been washed up on another shore; yet they had found a place of rest here, in an Edinburgh terrace with a sculpted pair of heron on the roof.

The small front garden was full of plants, closely tended, surrounding a rectangular patch of mown grass. Large windows gave passers-by a view right through the house into Jim’s rooms and to the Braid hills beyond. He never closed the shutters before nightfall. Sometimes before pulling the bell I hesitated, watching his careful movements, bent and slow, as he wrote at his desk. A tug on the cork sent the sprung bell swinging, chiming itself to a standstill.

Here was his last home, where he died in the Spring of his ninety fourth year, in his bed with three generations of offspring present.

After living in London, Paris, rural France, Morocco and Cambridge, he and his wife moved to his birthplace. Helen died in Jordan Lane; Jim spent his last years in Albert Terrace.

Jim opened his front door slowly. In his jacket and slippers he looked fine. Maybe his cheeks had white bristle but he wore an impeccable cravat, pinned by a silver brooch. He reached out both arthritic hands, held mine in greeting and smiled.

“Oh, you’re cold – come in.”

Into the hall with fresh flowers on a low wooden chest. From the blue curtain half-covering the door to his front room hung a cross on a thin chain – the George Cross, I think – usually hidden in folds. His feet shuffled as he led the way in and I stepped delicately, careful to enter respectfully. I took off my shoes and left them at the door.

He had explained how the space between furniture forms channels, a way of flowing. His bookcase could be a boulder around which paths split: so one walked through wide open doors and veered right, past plants and glass to a bedroom, or else swung left where the river narrowed into his tiny kitchen, with the cool still bathroom beyond… I was tender with these spaces, for clumsiness shows disrespect for the precision with which objects engage with each other, and with us. A pebble beside driftwood, and a candle holder on a cork – each found a meeting which could never be repeated. To pick up a brush was to enter its life; to place it again was another prayer. And in Jim’s hands everything found a place of true rest. Neither crowded nor lonely, but just where they seemed to belong.

This time I entered an especial stillness. Day was breaking, and the brightening thin blue sky’s light barely seeped inside. The air was warm, with the scent of pot pourri which filled an old wooden hatbox. Its rose petals came from Egypt, its lime blossom from Syria, and Jim flavoured it with French cognac.

Nothing moved except our arms in embrace. The fridge’s gentle hum was the only sound besides our breath, and my feet sliding in woolen socks on a smooth pine floor. I still carried some sleepiness and was glad to sit down – on a white-covered sofa beside rows of books. Lost Horizon by James Hilton, the Tao Te Ching, Saint John of the Cross and Winifred Rushforth’s Ten Decades of Happenings are the ones that I recall best.

I looked through the glass tabletop, as I put down my china teacup beside a cactus, and saw the wavy grain in a brown stool. Under a cushion wrapped in tapestry I found a pale stone, smooth and oval, which fitted the hollow of my half-clenched palm.

“Please come to breakfast now,” he invited, leading the way into his bedroom. As he nudged open the door Tibetan prayer bells swung on the door handle and their high resonant note shocked me awake.

Jim’s bed was draped in folds of a soft cotton veil, amber against the white of his bedspread. It seemed as if no-one could ever have slept in that bed, he made it so perfectly every morning. Above the bed was a huge black-and-white photograph of a Fra Angelico in which an angel plays the harp strings of Christ’s radiating halo as He dies. Mary supports His limp body and weeps. The rigid form of Christ’s arm, torso and leg is angular – Cubist, in fact, Jim said.

At the foot of his bed hung a picture on hardboard above a yukka tree.The wood showed ages of weather, layers of paint and green stains. Onto the discarded board Jim had brushed black ink, making (for me that time) a movement of sails across rough sea. And above that began a high shelf, running round the entire room to the tall window. Along it were leaning porcelain plates, a soup tureen and some saucers, patterned in cool cream on predominant rich blue. This blue often returned to Jim when in India, sweating out a fever in tropical heat.

A terracotta Buddha sat in a corner, sheltered in a column of bark. Framed on the wall beside Buddha, a fine pencil landscape was so faint that I focused on reflections in its glass. Then, concentrating, I discovered trees and clouds inside.

Before the window on an oblong mahogany table a feast was laid for two. Jim had peeled grapefruit segments and taken the seeds out of grapes to make fruit salad in delicate pale bowls pottered by Lucy Rie. A silver toast rack, a wooden butter dish, long thin hallmarked spoons to eat with, a sugar spoon-shell and a teapot were all composed as still life. Every object was a pleasure to look at and feel, and our food was delightful to taste. As we ate from this arrangement the composition came alive. The real beauty of his art, of the sculptures, crystals and flowers on our breakfast table, was how they gave life to ourselves as we breathed life into them.

The sky behind the Braid hills became vivid blue, brightened into yellow, then burned orange and gold as the sun rose up. A chorus of birdsong greeted the warm light which melted the frost on grass stalks and leaf tips. Our table swung into motion when long shadows fell in our laps. Sunlight warmed a smile inside me.

The sun lifted from the horizon with astonishing speed yet the shadows shortened and slid imperceptibly..

We talked of the past, of places Jim knew from a different age. He told me of Helen, how he had courted her love:

“I was an assistant at the Tate, an underling without parentage of much worth. She was a German who fitted in London society.” He was talking of the 1920s.

“I fell in love with her long before she noticed me. I wrote her letters – which she didn’t reply for some time – for seven years. Eventually I persuaded her that she loved me!” Jim paused and grinned, remembering the woman with whom he shared his life. They were married for over sixty years.

“I feel her presence sitting here in this room with me sometimes,” he whispered. And I thought I did, too.

He picked up a rough grey stone and it parted cleanly in his hands, showing a cavern of glittering crystal inside. “This,” he said, “may have been kicked open by a camel.” Leaving everything else to my imagination, he laid the open halves on the table.

We left the bedroom to sit on a sofa, now with strong sunshine on our backs. I saw a rainbow on the bookcase, cast by refraction through an octagonal glass beaker which scattered the sun’s light towering towards the skies. When I left the house I moved into a different world, one where people were battling against cold wind, pressing forward to their places of work. I turned and saw Jim at the window, waving goodbye.I felt refreshed and awakened; come what may, I knew that this day had been blessed.

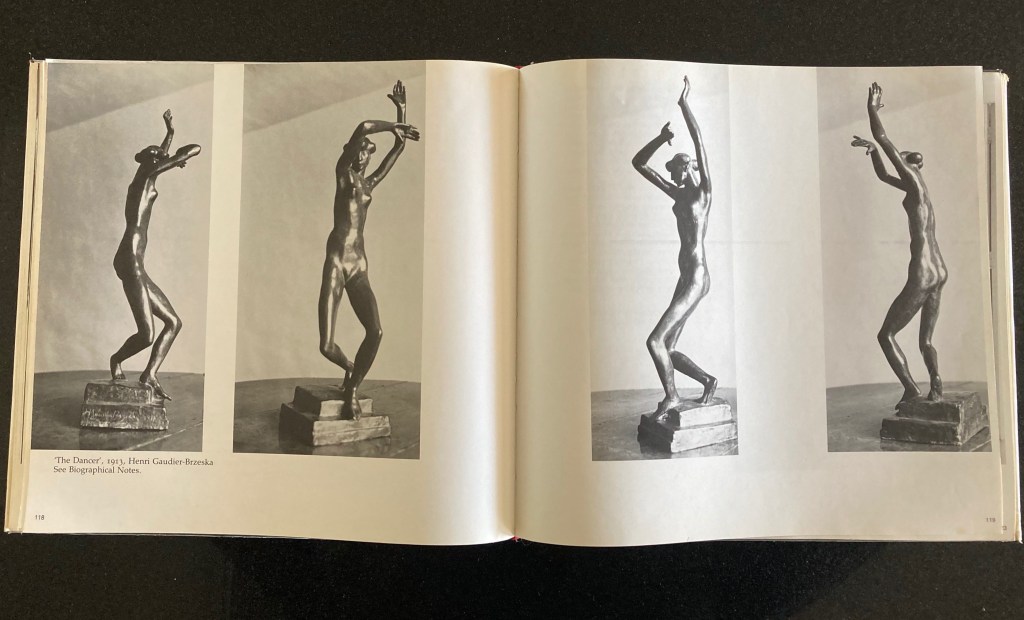

All images come from A Way of Life, by Jim Ede, published in 1984 by and © Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0 521 25062 5

SEE ANDY KIDD’S ELDER SPOTLIGHT HERE!

A Poem On Behalf of The Beauty Of Aging

BENEATH THE SWEATER AND THE SKIN

How many years of beauty do I have left?

she asks me.

How many more do you want?

Here. Here is 34. Here is 50.

When you are 80 years old and your beauty rises in ways your cells cannot even imagine now and your wild bones grow luminous and ripe, having carried the weight of a passionate life.

When your hair is aflame with winter and you have decades of learning and leaving and loving sewn into the corners of your eyes and your children come home to find their own history in your face.

When you know what it feels like to fail ferociously and have gained the capacity to rise and rise and rise again.

When you can make your tea on a quiet and ridiculously lonely afternoon and still have a song in your heart

Queen owl wings beating beneath the cotton of your sweater.

Because your beauty began there beneath the sweater and the skin, remember?

This is when I will take you into my arms and coo, YOU BRAVE AND GLORIOUS THING, you’ve come so far.

I see you.

Your beauty is breathtaking.’

~ Jeannette Encinias

Gratitude to BJ Garcia for passing this poem on to WildlyFreeElder. Look for her new Elder Spotlight SOON!

Losing It

What is “IT”?

Out of balance. Out of a carefully cultivated identity or pattern. Out of the minds attempts to make sense of everything or anything at all. Out of feeling a sense of groundedness. Out of control. Out of…..you fill in the blank.

Into chaos. Into rage and anger. Into deep grieving and loss. Into the unknown. Into the heart of uncertainty. Into the wildness of untamed expression.

The warning was clear as I watched the thick smoke from a wildfire only two miles away make its way towards my home sanctuary. The property owner informing me of what to do by turning my car facing out of the driveway with everything I needed for an imminent evacuation.

Never having experienced this before common sense, cultivated over a lifetime, came forth and gave my mind something to focus on. I don’t remember feeling fear, but instead acceptance of what one must do when presented with these circumstances. I had a place to go to that was safe and having simplified my life there was very little I needed to take with me.

The fire continued to be uncontrolled with high temperatures and wind driving it unpredictably. Landscape with beautiful trees and teeming wildlife was being scorched before courageous fire fighter’s eyes, valiantly doing their best to contain the fire in very challenging conditions.

Our area only one of so many burning uncontrollably, many losing their homes and animals – or their lives – amidst emergency evacuations. Within 24 hours I was able to come back home as the roads to the property were opened back again. The fire had shifted its’ course thanks to the amazing efforts of the fire fighters – and the shift in wind.

Staying on alert for sudden changes, and being ready to quickly leave once again if the fire changed course or became uncontrollable, I was to be one of the fortunate ones. But I didn’t’ know that at the time of evacuation.

Taxing an already vigilant nervous system trying to hold on from the fires devastation and subsequent air quality so poor one could not even walk outside, to the pandemic virus and home sheltering, racial injustice and violence, political chaos, the recent death of two beloved friends, losing employment, a move to a new location. Realizing that I had joined many others here in the U.S. and across the world reaching their own tipping point….. and falling over the edge.

In those moments I was to feel and experience that “Losing It” from time to time is necessary and can be an escape valve for stored up tension, anxiety and unexpressed emotion. For some of us who have identities cultivated as always “having it together” and always “being there” to support others, it can be scary territory and one where we feel naked and vulnerable. Is anyone listening or watching me?

In transparently sharing this experience with others it becomes a part of the collective permission. Leaping over the patterned excuse that you are more fortunate than many others so why should you permit yourself to lose it? Why shouldn’t you?!

Just like the fire that has scorched 1000’s of acres of California landscape there is a time for “raging” and clearing away the debris followed by regeneration. It is the way of nature….the way we maintain a semblance of balance amidst the rawness and fear of chaos and the unknown.

A way we restore the nervous system back to rest and renew. The landscape regenerates, we pick up the pieces of our lives and build them back again never to be the same. In tune with the ever changing impermanent landscape of our lives, nature and all living beings we are called to action.

Evolution in process, aging in process.

As we place our attention not on the chaos, but on what is most important in and to our lives and well being, as well as the collective – the heart centered actions we can take into restoring wholeness –